Discovering a New Species in Nevada

This morning, I had a new paper published on the beautiful darkling beetles in the genus Eleodes - commonly known as the 'Desert Stink Beetles'. In this paper I described a new species I discovered from doing field work in Nevada during the summer of 2015. When I tell people about my research, that I discover and describe new species of beetles, I am more often than not greeted with surprise and the question "I thought we knew all the species on the planet, how do you find new ones?" This blog post is my attempt to explain the process by telling the story of Eleodes inornatus Johnston, 2016.

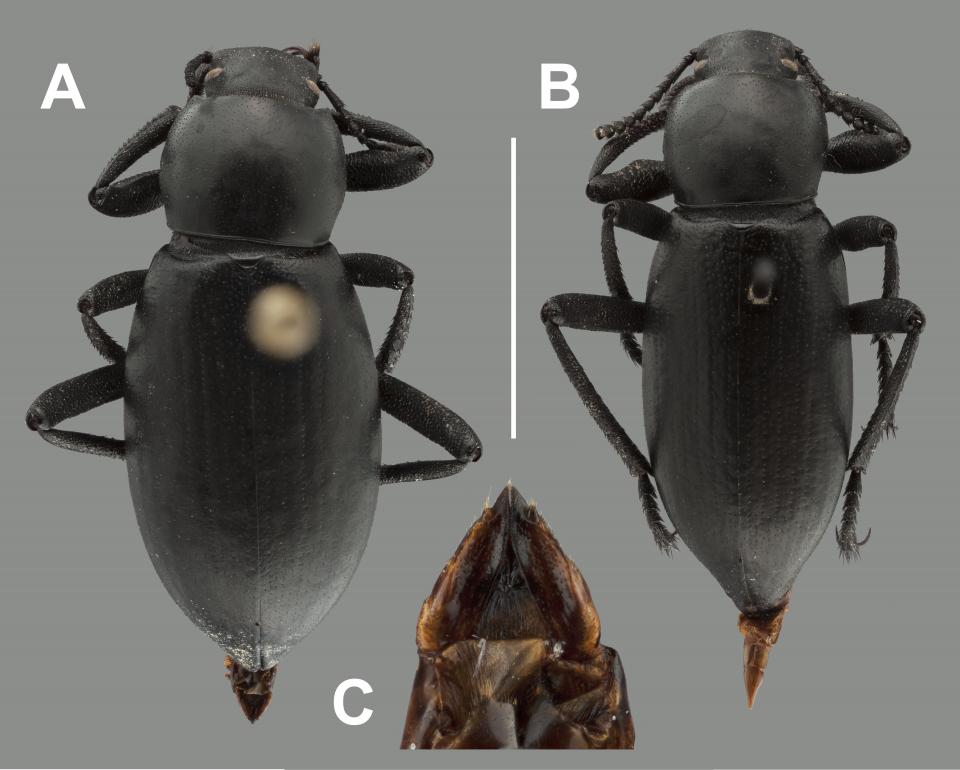

Eleodes inornatus Johnston- a new species

The two specimens in the image above are from the Type Series for Eleodes inornatus. The specimen on the left (A) is a female and is the holotype - that is, the specimen that anchors the scientific concept and latinized name Eleodes inornatus to the organisms that live in the natural world, it serves as the de facto definition of what this name refers to. The specimen on the right (B) is a male paratype - one of a number of specimens designated at the time of description which serve to expand the author's concept of the species.

Both specimens were collected on July 6, 2015 under bags of trash dumped on the side of a lonely 2-lane highway (Route 95, 17 miles North of Fallon, NV). I knew right away that these represented a species I had never collected before and I immediately preserved a tissue sample in alcohol so I could sequence its DNA later. My colleague Rolf Aalbu and I cheerfully argued about what these beetles might be as we collected a total of 4 specimens. The stop, which started as a break to find a restroom in the middle of the desloate Great Basin desert, took a total of 5 minutes which included flipping over the bags of yard waste and some discarded lumber which had ben unceremoniously dumped on the side of the road. We found 3 more specimens, two of which were recently deceased, that night at the Teel's Marsh sand dunes located about 20 miles SE of Hawthorne, NV.

Once back to the microscope in the lab, I was able to confirm that this species had never been described by the generations of scientists who came before me. I then began to look through other collections to see if anyone had collected it before. I ended up finding a single specimen collected near the Sand Mountain Recreation Area outside of Fallon, NV. This brought the total number of specimens up to 8, half of which were found under trash on the side of the road.

This is the story of just one of thousands of new species described in 2016, but I think it illustrates the two main components of species discovery: documenting biodiversity, and deciphering biodiversity.

Documenting Biodiversity

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is basically impossible to find something new if you have nothing to examine. This of course means that in order to find all the possible new species in the world we need a large number of samples to study. This can take many forms, from high resolution images to a small tissue sample. But for insects, like many other groups of organisms, collecting the entire specimen as a voucher is usually necessary for a scientifically useful record.

New species are often found in remote places like tropical mountains that require multiple day hikes to reach, but that does not mean we are finished documenting and discovering nature around us. Recently, 30 new species of flies were discovered in the city of Los Angeles. The key is to get out, look, and document what you find.

Field work can be a dirty and exhausting experience, but there is nothing quite like it! I am very grateful for the time I have been able to spend in the field and for the people who have accompanied me on my trips. Tens of thousands of insects have been collected and processed from the trips I have been on and have been placed in research collections and museums for future studies - and this is one of the outcomes of my graduate research that I am most proud about.

Deciphering Biodiversity

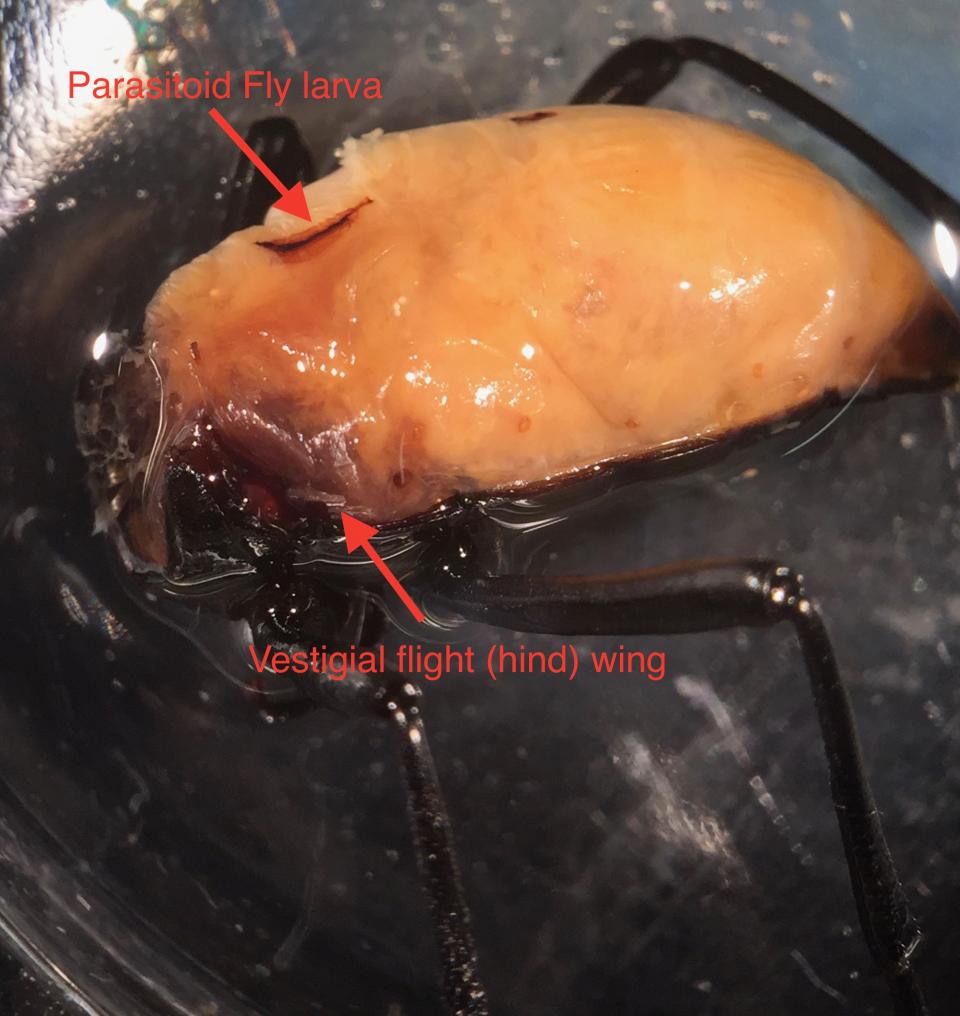

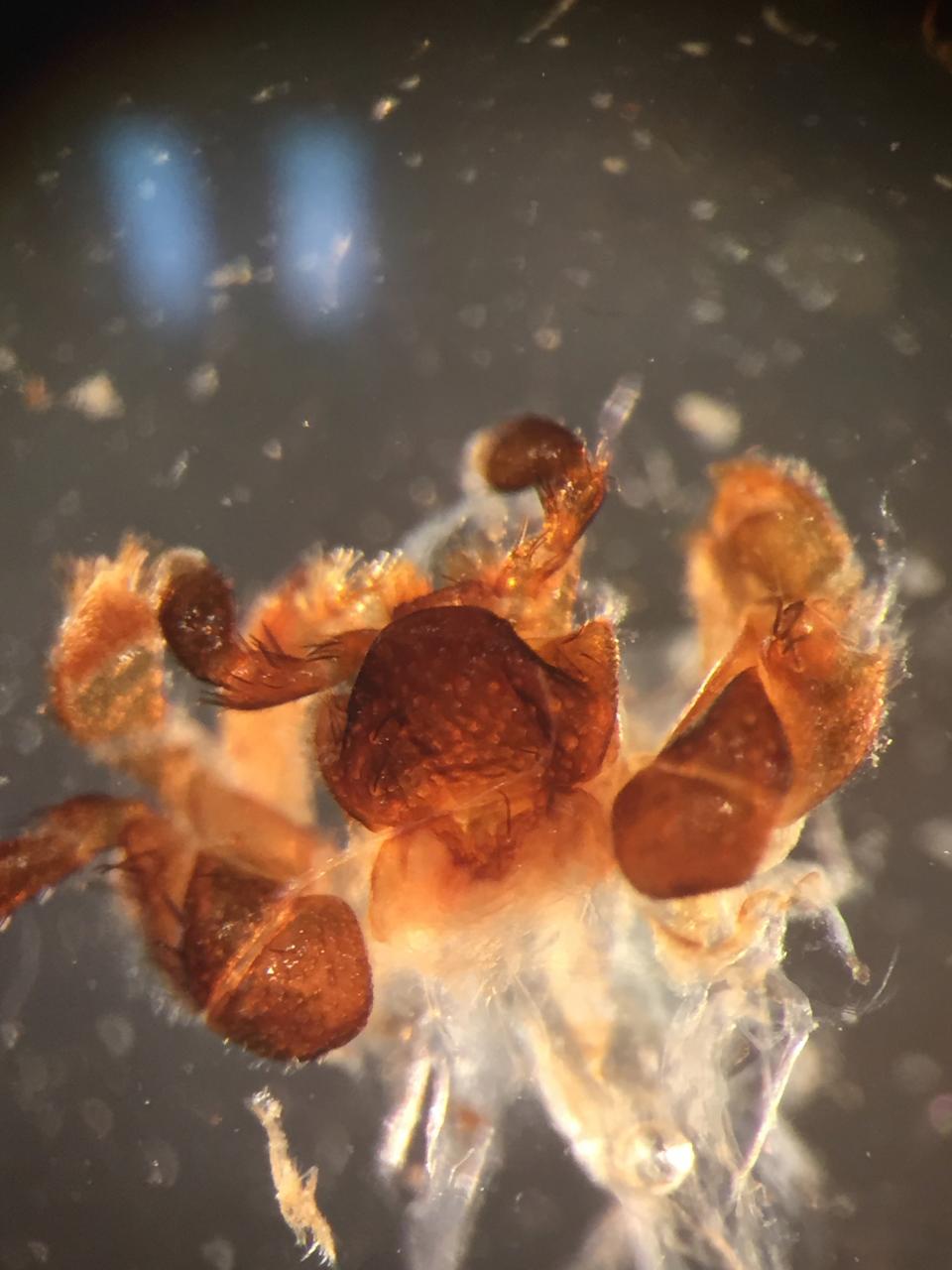

This bit might be a little more difficult, but is no less rewarding than working in the field. Once biodiversity has been documented, it must be analyzed. The first step is usually identifying what this organism actually is. This step could be as simple as using a field guide or looking at pictures on-line to compare to your sample or photo observation. But for many groups of organisms, this is a bit more complex. To know if a specimen is a new species requires knowing that it does not belong to any of the species already described. For groups like insects, this can very rarely be done from a photograph or DNA sequence, but usually involves close examination and dissection of adult specimens.

This is where the natural history collections become invaluable. Collections, along with scientific publications, not only hold our vouchers from nature but also the academic and intellectual legacy of natural historians who came before us. By comparing our unknown specimen to identified specimens we can begin to decipher the biodiversity we have documented. While external characters like size, color, and shape are very valuable, we often need to look at internal structures to verify the identity of many species.

We certainly have much to still discover about the natural world around us. Discovering a new species has been one of the most exciting parts of my research. Even though the study including this new species has been published, my work is not done. There are at least a dozen other new species from my collecting trips ranging from Oregon to Guatemala which are awaiting description, and many more out in the field just waiting for someone to come along and discover them!